From Notes to Narratives: Why the Future of Clinical AI Depends on Storytelling

Storytelling rarely announces itself while it is happening. In most contexts, it is not performed for effect, but for function. It is how humans compress complexity, decide what matters, and coordinate action under uncertainty. Long before we built formal systems or institutions, stories were how we aligned understanding, responsibility, and intent.

This may feel like an abstract place to begin a discussion about clinical documentation and AI. But that dissonance is intentional, because nowhere is our dependence on shared narrative more constrained, or more consequential, than in medicine.

Clinical Documentation Is Narrative Work

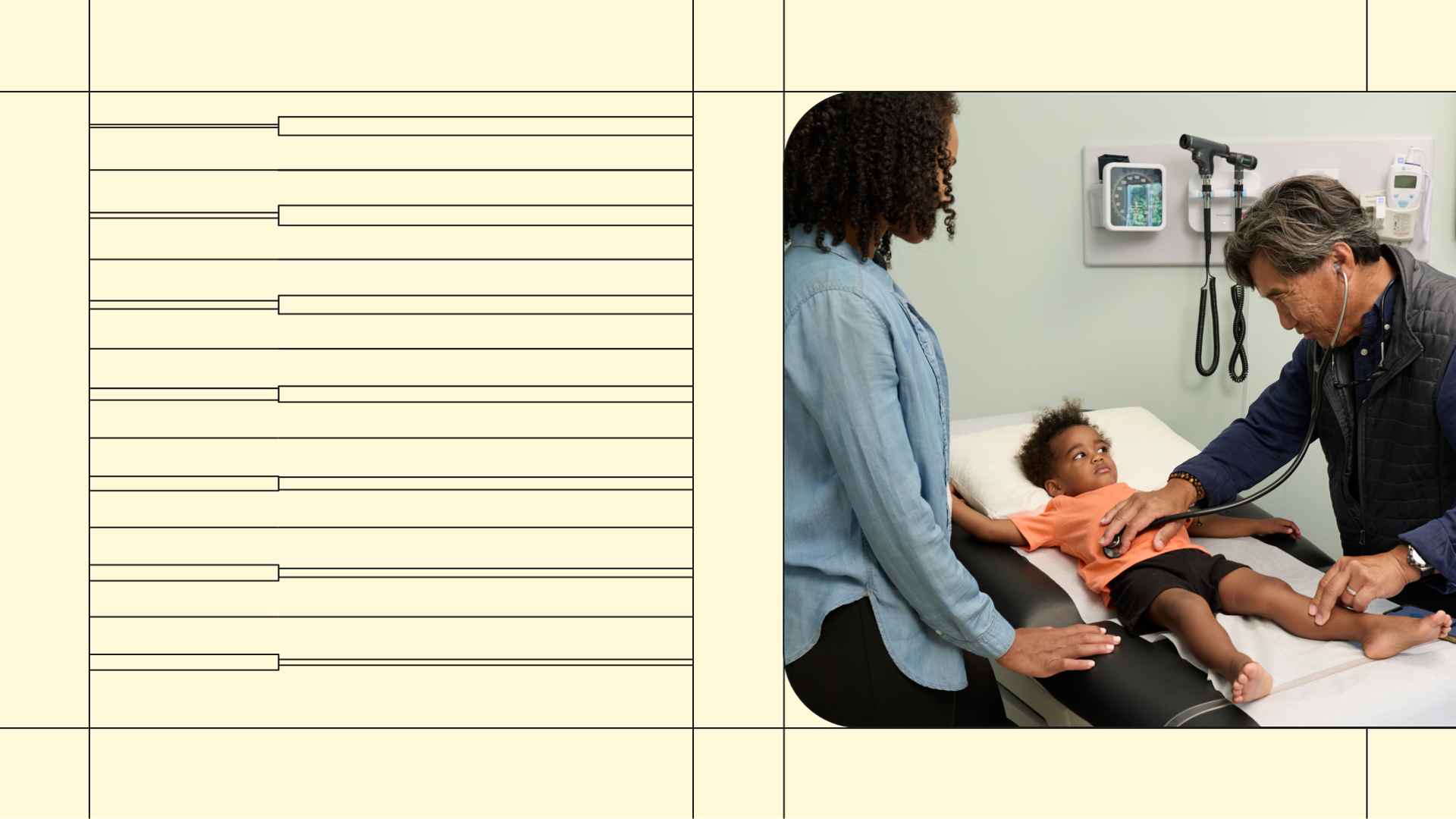

Clinical documentation is often described as a record of what happened. In reality, it is an act of translation. When clinicians write notes, they are not simply enumerating facts or transcribing events; they are constructing a story that allows another human being (often someone they have never met) to understand what has happened, why it matters, and what should happen next.

When documentation works, it feels intuitive. When it doesn’t, it feels dangerous. The difference is not correctness, but coherence.

At its core, clinical reasoning is narrative reasoning. Clinicians think in timelines, not tables. Illness unfolds over time: symptoms begin, evolve, respond, or fail to respond. A fever that started three hours ago means something very different from one that has smoldered for weeks. A patient who worsens after an intervention tells a different story from one who slowly improves. Temporality, what happened first, what changed, what persisted, is not decorative detail. It is often the diagnosis.

Closely tied to time is causality. Clinical notes are filled with subtle signals of intent: given, because, likely, concerning for. These are not stylistic flourishes. They encode the clinician’s reasoning; what they believe is driving the patient’s condition and why a particular decision was made. Two notes can contain identical facts and yet communicate entirely different levels of urgency depending on how causality is framed. One tells a story of watchful waiting; the other, of impending deterioration.

Other narrative devices matter just as much. Emphasis guides attention when time is short and stakes are high. Omission reflects judgment rather than neglect; benign findings are often left unstated precisely because they are unremarkable. Point of view shifts depending on whether the note is written for handover, consultation, or medico-legal record. And uncertainty (far from being a flaw) is a signal that helps downstream clinicians calibrate vigilance and risk.

These are not abstract concepts. They shape real workflows every day: how clinicians hand over patients, what tests they order, how they interpret results, and how continuity of care survives despite rotating teams and fragmented systems.

Seen this way, the clinical record is not a passive archive. It is active infrastructure: a thread that connects one decision to the next. Its primary function is not to store data, but to preserve meaning across time, people, and uncertainty.

When the Story Breaks

I learned the importance of this early in my training, while working night shifts on a surgical ward.

The patients I worried about most were not the sickest or the most complex. They were the patients whose story I could not reliably reconstruct. I was working for a very talented surgeon, thoughtful, diligent, deeply committed to her patients. She worked late, rounded personally, and documented her thinking carefully. The problem was not competence or effort. It was that the documentation, once committed to paper, was almost impossible to decipher.

On day shifts, this was an inconvenience. On night shifts, it was something else entirely.

When I was called to see a patient overnight, the first thing I did, as any on-call doctor does, was read the notes. I needed to know what had happened, when it had happened, why decisions had been made, and what was expected to come next. Often, I couldn’t. The story had been written, but it was locked away from me. The handwriting resembled a patient whose EKG was flatlining.

That left me with one of the hardest calls in medicine: whether to wake my senior at three in the morning. Not because a patient was crashing. Not because I needed clinical advice,but because I could not decipher the story well enough to make a safe judgment on my own.

This is the paralysis that broken narratives create. Not a dramatic error, but hesitation. Not ignorance, but uncertainty about what matters. Electronic medical records have largely solved the problem of illegibility. They have not solved the deeper issue this experience exposed: that safe clinical judgment depends on access to a coherent story.

Why This Is So Hard for AI

It is tempting to assume that clinical documentation is difficult for AI simply because medicine is complex. That explanation is comforting and incomplete. The deeper challenge is meaning.

Humans are exceptionally good at inferring meaning from incomplete information. We do this constantly, often without realizing it. When a colleague says, “I’m a bit worried about this patient,” we understand the implication without needing a probability score. When a note reads, “stable, but…,” we instinctively slow down. These interpretations rely on shared context, experience, and an intuitive sense of relevance.

AI systems lack this intuition not because they lack sophistication, but because meaning in clinical care isn’t always explicit. Linguists describe this gap as the difference between semantics and pragmatics, between what is said and what is meant (Grice, 1975). Clinical documentation operates heavily in this pragmatic space.

This difficulty is well described in classical AI research as the frame problem: determining which aspects of a situation are relevant and which can safely be ignored (McCarthy & Hayes, 1969). Humans resolve this through experience and responsibility. Clinicians know, often instinctively, which details matter in a given moment. AI systems must infer relevance indirectly, from patterns in data, when importance is signaled through emphasis, omission, or structure rather than explicit labels.

Another useful lens is compression. When clinicians write notes, they intentionally perform lossy compression: distilling a complex, high-dimensional reality into a narrative that preserves what matters for future decision-making. The goal is not perfect fidelity to every detail, but preservation of meaning.

Modern AI systems, particularly large language models, have become increasingly good at capturing the surface form of this process. Transcription accuracy, factual correctness, and detection of hallucinations or omissions are real advances and essential foundations. Without fidelity, no meaningful narrative can exist.

But fidelity alone does not guarantee meaning.

A transcript can be accurate and still fail to preserve the clinical story. A note can be complete and yet obscure what matters. A fluent summary can flatten uncertainty, subtly changing how downstream clinicians interpret risk or urgency. These are not failures of correctness, but failures of prioritization and intent.

This reflects the symbol grounding problem (Harnad, 1990): words acquire meaning through use, experience, and consequence, not symbols alone. For clinicians, phrases like concerning or low threshold to escalate are grounded in accountability. For AI systems, they are tokens whose significance must be inferred unless explicitly modeled.

Implications for Design: Preserving Narrative in Automated Systems

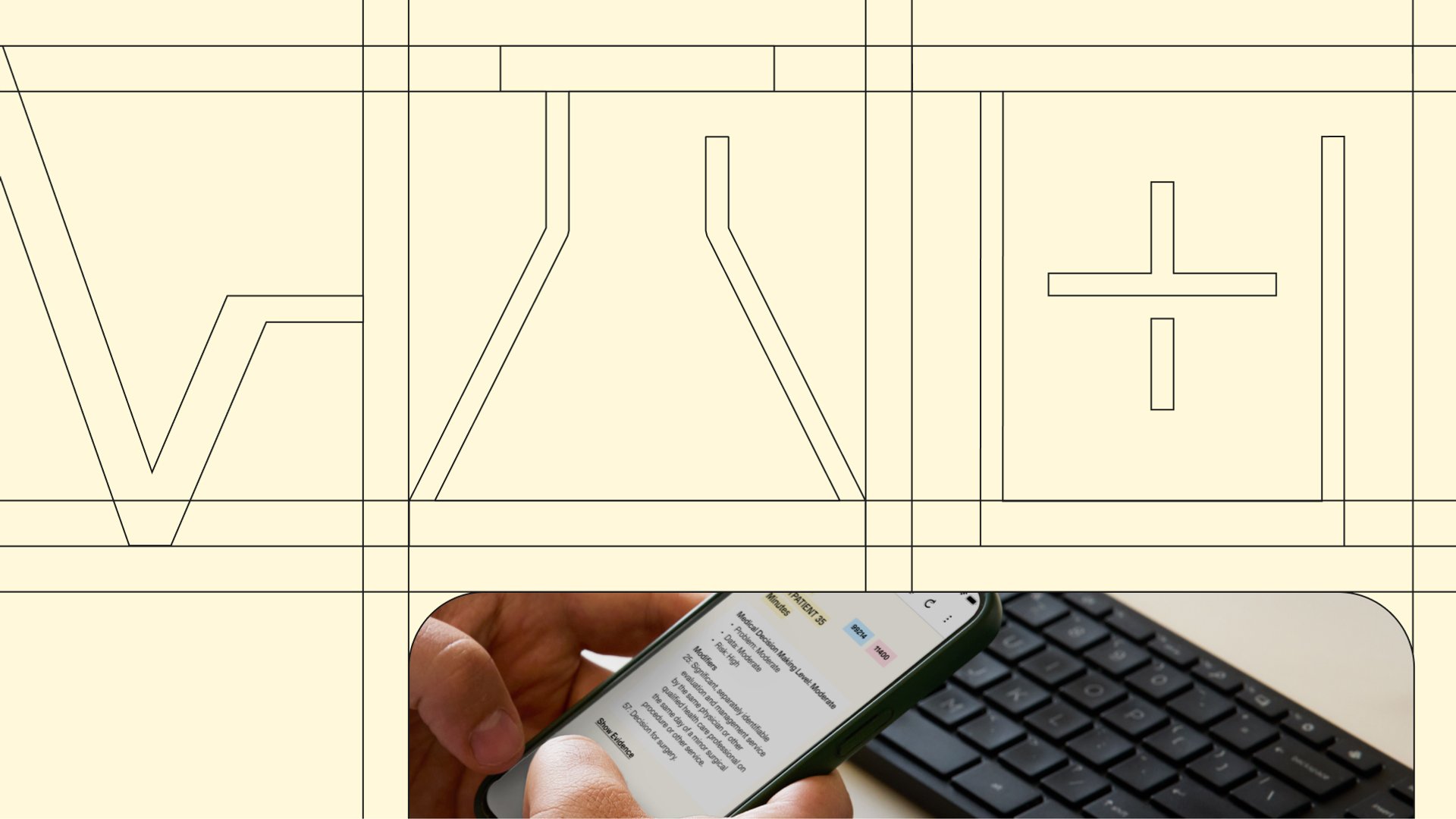

If narrative is essential to clinical meaning, then clinical AI cannot simply be a passive mirror of a conversation; it must be designed to preserve the "story" explicitly. This requires moving beyond a simple "text-in, text-out" model toward a system that respects the clinical geography of a note.

- Scaffolding over Spontaneity: Rather than relying on unconstrained text generation, which risks drifting from the truth, generation should be scaffolded. By using intermediate structures, like timelines and problem-based outlines, we ensure the AI mirrors the way a clinician actually reasons.

- Time as a First-Class Citizen: Narrative depends on progression. Systems that flatten chronology risk obscuring the very urgency they are meant to capture. A fever that started three hours ago is a different story than one that has smoldered for weeks; the AI must treat that sequence as sacred.

- Structured Semantic Layers: High-quality design uses ontologies and knowledge graphs as the "bones" of the note. This structure doesn’t replace the human story; it supports it by making the relationships between a symptom, an intervention, and an outcome explicit and auditable.

- Preserving the "Hedge": Clinical language is rich with probability and contingency. Design choices that "smooth away" uncertainty for the sake of a clean read actually reduce safety. If a clinician is "concerned for" a condition, that nuance must survive the transition from voice to page.

The shift here is subtle but vital: we are moving from treating notes as mere text to treating them as structured stories.

Implications for Evaluation: Measuring Whether the Story Survived

Evaluating narrative preservation requires a layered assessment that looks past surface-level fluency. Foundational metrics like accuracy and completeness are non-negotiable, but they are only the starting point; they do not tell us if the note is useful.

True clinical AI rigor requires measuring dimensions that reflect the reality of care:

- The Logic of Inferences: Not every "addition" is a mistake. We must distinguish between logical deductions—conclusions that can be safely derived from the evidence—and unsafe leaps that change the medical intent.

- Precision of Presence and Absence: Evaluation must account for both "hallucinations" (adding what wasn't there) and "omissions" (leaving out the critical subset of facts that matter). Identifying a missing "critical fact" is often harder than spotting an error, as it requires an understanding of what should have been said.

- Task Utility: The ultimate test of a note is whether another clinician can safely act on it. This mirrors how we evaluate medical trainees: we don't just check their spelling; we ask if their story supports sound decision-making.

- Structural Integrity: Even a factually perfect note fails if the information is in the wrong place. We evaluate whether the "clinical flow" is maintained, ensuring that subjective reports don't leak into objective results.

Where Suki Fits

This is the landscape in which ambient clinical AI now operates. Suki’s approach is built on the belief that documentation is not just transcription, but contextual reconstruction.

By combining ambient capture with deep EHR integration and specialty-specific workflows, Suki aims to preserve the clinical story rather than overwrite it. This means treating accuracy not as the endpoint, but as a prerequisite for something deeper: a system that respects longitudinal context, honors clinical uncertainty, and aligns with the intuitive way doctors think.

Narrative does not live in a single encounter; it lives across the entire continuum of care. This is why partnerships across health systems and vendors are so critical. As AI becomes embedded in practice, our goal is to ensure that precision and understanding evolve together, ensuring that technology doesn't replace the human act of care, but reflects it more faithfully

Closing Thoughts

Clinicians have always known that accurate information is not the whole story. Care happens in the space between measurement and meaning; between what is recorded and what is understood. As AI becomes embedded in clinical practice, the challenge is not simply to write notes faster, but to ensure that precision and understanding evolve together.

When they do, technology does not replace the human act of care. It reflects it more faithfully.

References

- McCarthy, J., & Hayes, P. (1969). Some philosophical problems from the standpoint of artificial intelligence.

- Grice, H. P. (1975). Logic and conversation.

- Harnad, S. (1990). The symbol grounding problem.

- Patel, V. L., Arocha, J. F., & Zhang, J. (2005). Thinking and reasoning in medicine.

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow.